Henry Inlander: A Personal View

Inlander was a landscape painter who died in the 1983. More recently, his widow, Antonia Inlander died in a place she and he loved, Anticoli Corrado, which is a small, beautiful town in the mountains to the east of Tivoli and Rome, Italy. This short essay is about Inlander's work.

“To live within the landscape is of importance to me; not that I would set up an easel in it but simply the daily contact would further my understanding.” (Henry Inlander)

Anticoli Corrado, early morning

Fragments of experience can be brought together by colour and shape, form and canvas, but also by craft and an intense awareness of the visual arts as one of the foundations upon which humans build their understanding of the environments they inhabit. Paintings of landscapes bring the richness of the physical world into contact with human vision and the imagination.

Henry Inlander understood this eruption of the real world onto the canvas and this is best exemplified by his early drawings which explore everything from the textures of trees to the shape of a mountain against the sky. As an artist he was obsessed by the transformative power of art and by an inner impulse that made it impossible to live without creating, imagining and recreating the world that he loved. The fact that so many of his paintings portrayed the landscapes in and around Anticoli Corrado attested to his attachment to the hillsides, mountains, sky, people and all of the elements that make up this beautiful place.

His works are about an inner space of reflection and thought. He never painted or drew ‘in situ’ but instead worked from memory and his own imagination. Crucially, many of his paintings are related to each other, as if they were part of a series or a longer narrative. All of his work seems to foreground new ways of seeing objects and people. In fact, although elements of nature remain in his paintings, it would be more accurate to say that the transformative nature of his art recasts not only what he paints but also the manner in which spectators look and see.

He was driven by many profound and conflicted emotions derived in large measure from a family history that was marked by diaspora, and characterized by displacement and loss, including the death of some members of his family in Auschwitz during the Second World War. This intersection of history, personal experience and World War II and this combination of death, destruction and hope infuses all of his paintings with an urgency born of the desire to give substance and form to memory. At the same time, Inlander’s work rejoices in the beauty and simplicity of nature and in the many ways in which nature shapes not only human vision, but also human creativity.

Some artists have a deep sense of the physical world we inhabit and a rare few are able to depict that world as if it is alive and in constant transition. His paintings are always moving as if a cloud is about to pass overhead or as if a storm is just on the horizon. His was not an art of stillness; it was an art of motion and an art of the natural environment undergoing change and transformation. At the same time, there was a special kind of romanticism to his belief in nature, a romanticism founded on the naïve feeling that colour and shape can bring a transcendent quality to a natural environment that has to varying degrees been overwhelmed by human beings.

Inlander’s work is at the boundary of the figurative and the expressionist. In some of his paintings the landscape disappears into abstraction dominated by texture and colour, always in the service of the concrete and of his vision. Windows appear in many of his paintings, as do images of his wife. The inside view of a house is framed by an exterior landscape. It always seems as if the outside and the inside are going to merge, as if the paintings are layered by time-present and time-past, by what he has seen and what he has imagined. The prevalence of windows in many of his paintings is also a framing device, a modernist play on self-reflexivity and the search for meaning. Amidst his paintings one often notices details like blades of grass or the shape of a dog, and this tension between the real, the seen and the imagined plays itself out continuously throughout his entire oeuvre.

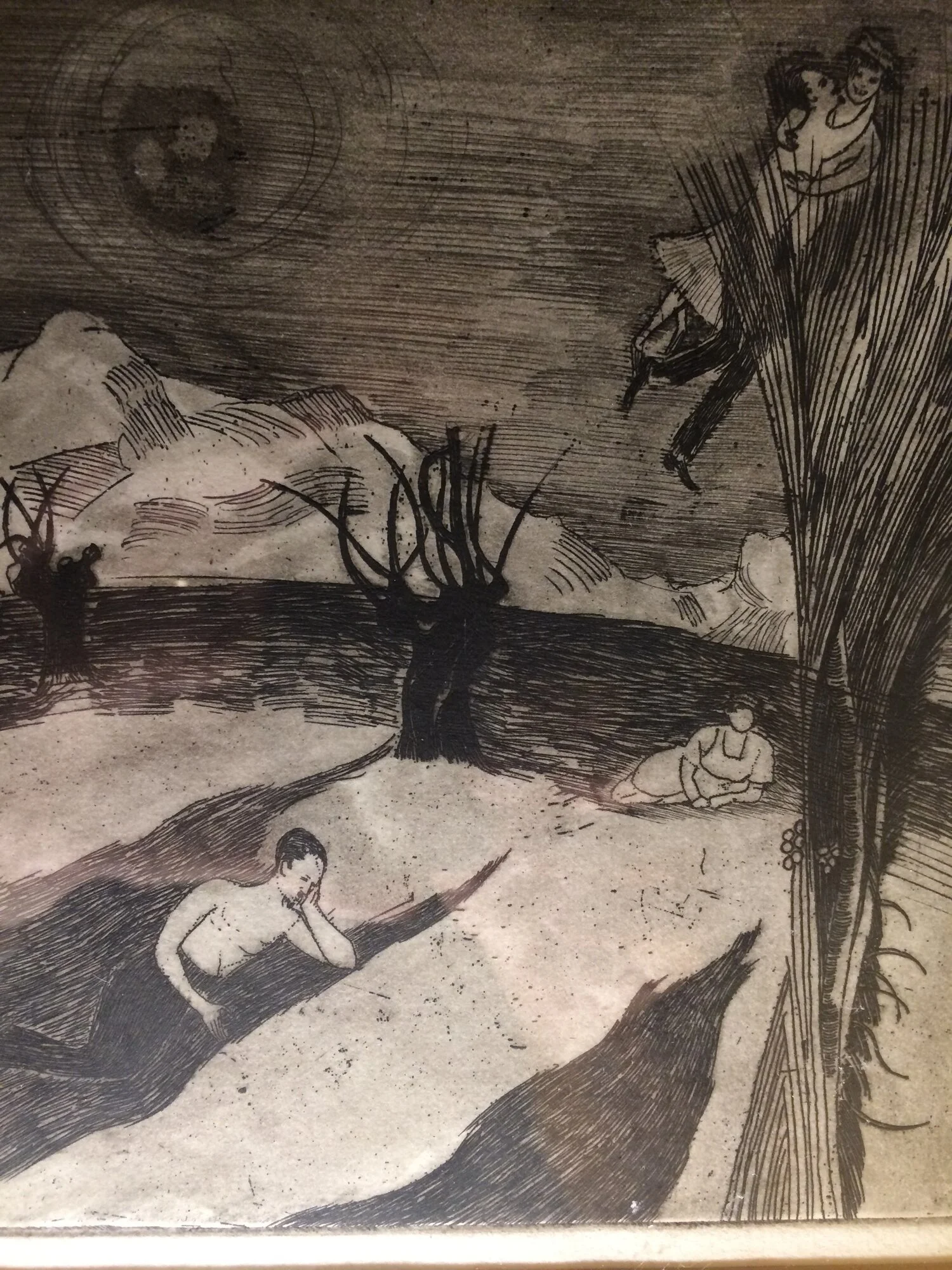

Some of his earliest drawings suggest a tension between reality, imagination and landscape. These drawings from the 1950’s hint at his love for Marc Chagall; they have a surreal quality that is unified by the figures in many of them, including a figure that is clearly a representation of the artist. In fact, throughout his career, the anxiety between figuration and fantasy makes its way into all of his art. This pressure transforms a night sky, for example, into a green canvas with white dots suggesting the connections between the earth and the heavens. “The ambiguity of shapes is a constant source of excitement to me. Landscape is only a pretext for the idea of an ideal world disrupted by visual elements, just as our world is disrupted by death, cruelty, Vietnam, Biafra.” For Henry Inlander, nature is more of a jumping off point for speculation, for poetry, for visualization than it is for duplication or copying.

Henry Inlander, Untitled, 1956

As a young child growing up in Vienna in the 1920’s and 1930’s, Inlander experienced the best and worst of Austria, from the cultural explosion of the 20’s to the Great Depression and then of course, the embrace by Austrians of Nazism. He and his family moved to Trieste in the middle of the 1930’s where they settled and learned Italian. A few years later as Italy spiralled towards Fascism, he and his family left for England. That experience, as well as living through the war in a London under constant bombardment, had a profound impact on Inlander’s art and career.

But it was ultimately Italy and Anticoli that meant the most to him and inspired so many of his paintings. It could be argued that a small village some 80 km to the east of Rome was as far away as possible from the traumas and pain of the worlds he lived in and came from, but that would not do justice to his work as a teacher in both London and Rome and to the impact he had on the people he was closest to, from his colleagues to his students.

Inlander, Self-portrait, 1957

© Ron Burnett

In the late 1950’s, Dennis Farr, an art critic for The Burlington Magazine which is still published in London, said with reference to an upcoming exhibit by Inlander: “a whirling storm-drenched alpine landscape by Henry Inlander confirms the promise of earlier work, combining something of the atmospheric delicacy of a Turner and the expressive force of a Kokoschka landscape” (Vol. 101, No. 676/677, 1959 304-305). It is of some significance that Inlander’s first one-man exhibition at the Galleria La Tartaruga in Rome in 1953 was followed by a major one-man exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in 1956. Tate Britain has four of his paintings in their permanent collection. Bryan Kneale, who shared a studio with Inlander on Fulham Road in the 1960’s, said the following: “He is a painter who has devoted many years to the process of creating a vocabulary, personal and original which enables him to encompass a very large field of visual experience, an essentially lyrical artist but also one where the darker side is never completely absent” (from the catalogue of an exhibition held at the Arts Centre in Folkestone in January of 1976).

Inlander, Woman and Dog, 1966

© Ron Burnett

The great Austrian poet Erich Fried compared Henry Inlander’s work to Turner and Pollock. Somewhere in between the polarities represented by these two painters sits an artist for whom the act of creative engagement was as vital to his everyday life as every breath he took. Inlander never adhered to one particular school of painting; he rebelled against the constraints of the art world and developed a style that uniquely expressed his vision of the world. His paintings and drawings are a haunting reminder of the transformative potential of all art, and for those of us privileged enough to engage with his work, they are a rich sign of the importance of visual art to all our lives.